In the mid-1940’s at LACMA’s original Exposition Park site, Hans Burkhardt’s painting, “One Way Road,” was removed from an exhibition because he used too much red paint and, well, it was deemed to be communistic. . Not strange for an era when abstract artists were sometimes suspected of being enemy agents cleverly encrypting secret military site locations into their art.

Jack Rutberg has been one of the most passionate and dedicated promoters of Hans Burkhardt’s work since the 1970’s, and it is not surprising that this artist is his gallery’s contribution to the “Pacific Standard Time” project, along with a room devoted to works by Claire Falkenstein. The Rutberg Gallery exhibit will run through December 24. Viewing this exhibit was a wonderful opportunity to discover the magnificent journey of Burkhardt, an artist shamefully neglected and in great need of rediscovery, an artist who helped reshape Los Angeles from an artistic backwater to what it has become today.

Rutberg has hung the show chronologically and selected samples from every period of Burkhardt’s long career in L.A., so that the viewer clearly sees the art movements that informed and influenced his art: post impressionists, cubists, fauvists, surrealists, and finally abstract expressionists.

Burkhardt was born in Switzerland in 1904,the same year that Arshile Gorky and Willem de Kooning were born. After an unhappy poverty-ridden childhood, he immigrated to America in 1924 and settled in New York about the same time as Gorky and de Kooning. Studying under Gorky, a deep friendship developed between both artists until Burkhardt left New York. From 1928 to 1937 they shared the same studio, even working on two joint paintings.

Due to a difficult domestic situation with his former wife, Burkhard left New York for Los Angeles in 1937. This pivotal move raises many “what if” questions. Would Burkhardt have been as iconic as Gorky had he remained in New York? Might he have been able to prevent Gorky from hanging himself? And had Gorky lived as long as Burkhardt, would their art have resembled each other’s?

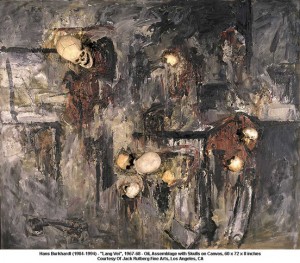

Once in LA, Lorser Feitelson arranged a solo exhibit for Burkhardt at the Stendahl Gallery (examples of his catalogs and show announcements are exhibited in the Rutberg Gallery). After that, he showed continuously throughout the 1950’s and ‘60’s, including four Whitney Museum Annuals. During that period he traveled to Mexico for extended periods of time and this became a significant period in his artistic life. Much affected by that nation’s high mortality rate and social treatment of death, he focused his paintings on existence and spirituality. In addition, the tolling of the church bells caused him to explore synesthesia, a situation where the stimulation of one sense, in this case sound, triggers another sense, the visual. In a catalog on Burkhardt, Margarita Nieto mentions his writing that “…I painted the soul of Mexico…the idea that there was something better thereafter.”

In 1959 Burkhardt started teaching and by 1963 had a position at California State University at Northridge. It was a rare opportunity for art students of that time to experience and receive instruction from such an active and passionate artist.

To understand Burkhardt’s paintings, one has to appreciate the duality of his subject matter. Rutberg, who developed a friendship with the artist, remembers him referring to his paintings as either “the fierce ones” or “the happy ones.” Burkhardt needed external events as motivation in making art; therefore his paintings are strong reactions to, even protests of, wars, and social injustices he saw around him: “the fierce ones.” Other paintings reflect his lifelong love of nature, his affirmation of hope, and his sense of the spiritual: “the happy ones.” But the viewer should keep in mind that this duality was always part of a single coin.

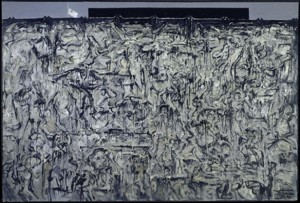

There are certain constants throughout his works. There’s solidity in all of them; nothing is ever timid in his handling. There’s an ever-present kinetic energy that permeates everything he painted. His paint application teeters between formality and spontaneity. There is a constant progress towards mixed media and replacing forms with thick impasto mixes. As time goes on, his paintings get larger and his sense of independence always increases. But perhaps upper-most, he never loses his strong expressionism; in fact, I would label him an Abstract Expressionist’s expressionist. To Burkhardt, abstraction was simply a box that held the message to be conveyed expressionistically.

As one turns to leave the gallery’s last exhibition room, a lone painting can be seen high over the room’s doorway. This work is entitled “The Extra Stripe” and is from his “Black Rain” series painted in 1993; it was his last painting. It consists of three charred wooden black crosses (war graves and/or Calvary) under a large stiff flag with alternating black and reddish stripes except for a white stripe at the bottom signifying hope. To the very end, Burkhardt’s duality—hope and despair– remains juxtaposed. In a 1992 “Art in America” review, Peter Clothier fittingly wrote that his paintings were “…astonishingly energetic…elegiac in tone…works of considerable art-historical complexity.”

I have (7) H. Burkhardt prints from the early 70’s. My father must have obtained them when he was Head of the Art Department at Cal State Northridge from 1969 to 1971. We greatly enjoy them.